Parker’s Note: Here’s a story by Christopher Ruocchio that I’m sort of licensing for Sages, Mages, and Wisdom Machines. Christopher is a friend and a fantastic author. You will know him from the Sun Eater science-fantasy series (and maybe even from his appearances on my podcast, Parker’s Pensées—but most likely from the books). This here is the first story of his newest hero, Adaman. Check out more from Christopher at his Patreon page here and watch our latest podcast episode here:

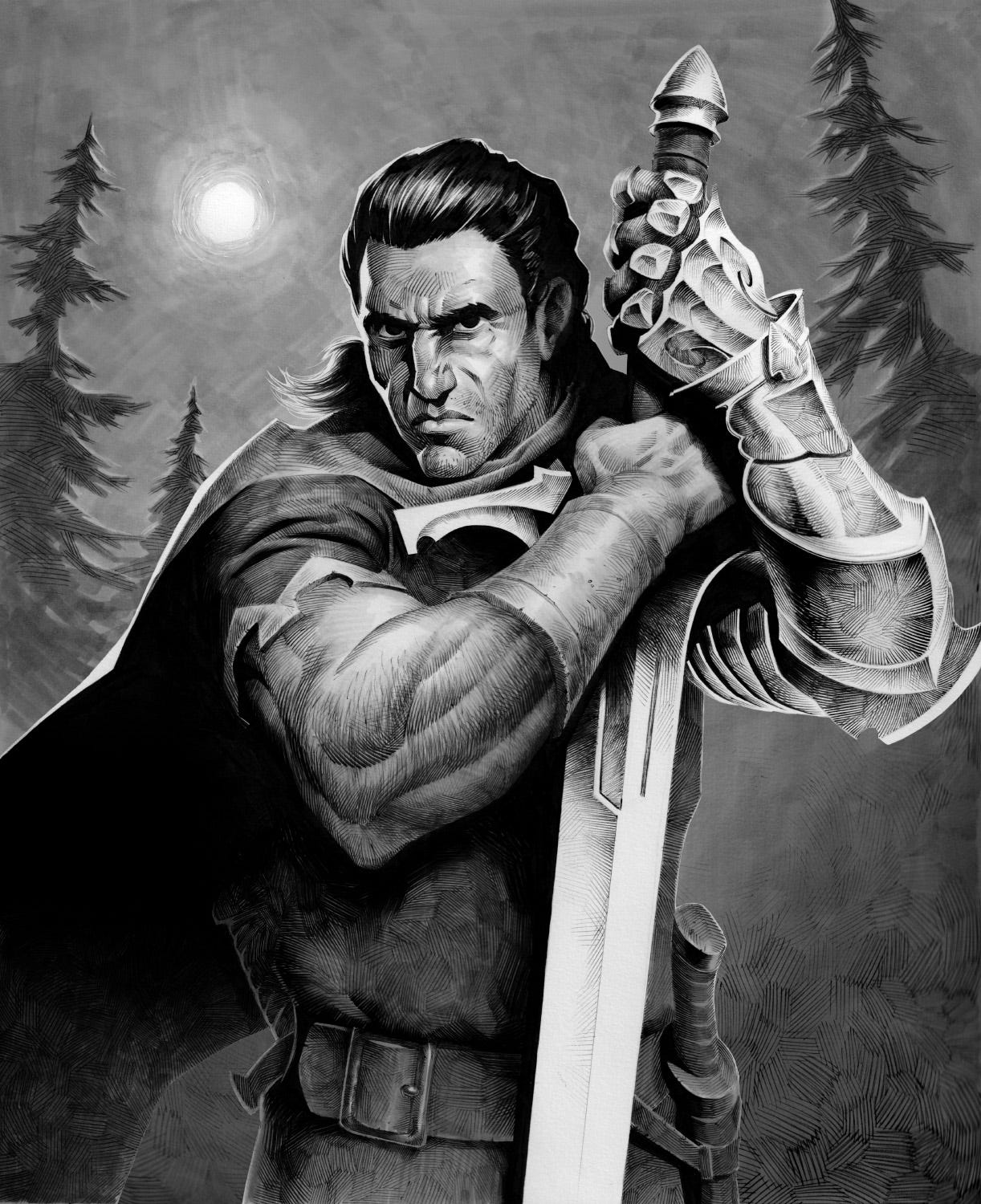

I commissioned the same artist that Christopher has been using for his other Adaman stories, for this post. The artist is Kevin Keele and he’s fantastic. Check out his instagram here and his Artstation here.

Please do go check these fellas out. Their work is fantastic.

I love artists. Many of them are being completely wrecked by AI right now. I’m committed to never using AI art for any of my SFF stories. It’s a pleasure to support real artists like Kevin and Christopher. So, if you like supporting artists, and you like my Sages, Mages, and Wisdom Machines project, then help support me so I can keep supporting other artists as well. Commissioning original artwork is really expensive. But it’s worth it. Help me continue doing it. Consider becoming a paid subscriber:

Alternatively, if you just want to say thanks without a monthly commitment, consider buying me a coffee:

Now please enjoy The Barrow King.

The Barrow King

A chill wind chased through the evergreens, made them bend and scrape before the coming of the lone hunter that walked in their midst. The forest seemed to him half a temple, one built to honor some unremembered god. Above the sky was growing dark. He did not relish the thought of making the return journey—back down the craggy face of the rock—after nightfall. He did not relish the thought of making the return journey at all. Not after he did what he had come to do. The villagers would not thank him for it, though he saved their children—and their lives. Adaman picked his way up the slope with care, moving with the ease of long practice. He had been alone in the wilderness a long time, and was little stranger to such climbs. So much of these southern lands—where the sun was cold—was given over to such crags, to canyons, mountains, and ridges of black stone. He only wished he still had his Solva with him. She could have managed the slope with little difficulty, but the nameless horse he’d ridden more than a thousand leagues out of Hakansa would have broken a leg for certain had he not left her on the gentler slopes behind. He heard her knicker in the woods below, imagined she tossed her head. Looking back, he could not see her. That was well. He did not want his quarry finding her—prayed they had not heard. He had not dared leave her in the village. After all, they were from the village. These men he’d come to kill. He cleared the trees as he reached the top of the ridge, for even the hardy fir trees of the Gurrandhi Highlands could not grow in rock. There Adaman halted, surveying the world. All the earth—which the priests of the House of Morn called Rök—seemed unrolled beneath him, though the mountains of the Din Gurrandh rose all around, black pillars—snowcapped—holding up the sky. He had not climbed high enough to see the Grand Wall away to the west, thousands of miles away—nor could. But he could see over the broken lands through which he’d traveled. There was the river the villagers called the Greenbend, where it flowed down out of its highland vale and ran north to join the great river that ran all the way to the Sea of Rhend. Away to the east, the land was a sheet of gnarled black stone—not the godstone of which the Walls were made—but common basalt. There the lavas flowed freely, gleaming rivers of fire steaming where they met the southern snows. Adaman hardly saw them. His eye was drawn—as ever—to the eye. The God’s Eye. The red moon hung almost directly above him then, the great eye that the gods had fashioned on its face with stones vast as kingdoms peering down, forever unblinking. Seeing it filled Adaman with disquiet, as it ever did. But there—almost on the edge of sight—was a thing that fanned the little ember in his heart to old flame. A ship. A black ship. It moved on the upper airs, kept aloft by its twin tanks and countless rotors, like a paper dragon, black and red and gold. He was certain that it belonged the Empire. To Qorin. His old masters. His enemy. They’re coming further south every day, he thought darkly, but put it from his mind. The Empire was far away. He had other troubles, and seeing them, pressed himself flat against the top of the ridge. He had found them. And found the place. Rigmardra, the locals called it. Kingsbarrow. There had been kings in that country once, or so the villagers had said. Great kings and terrible. Adaman knew not what their names had been, or what name their shadowy kingdom once claimed. Had they been men, those kings? Or neirtings, haelings, or elderkin? He did not know for certain that they’d been kings at all. But he knew there were nine, could count them from his place on the ridgeline. An auspicious number, by the reckoning of some. Nine were the Sons of Mor by the Great Mother, and Nine their sister-wives… Each mound was greater than the last, each covered in a carpet of grass and wildflowers. The place might have been beautiful—placid, serene—were it not for the shadow on Adaman’s heart. He knew such places, had entered into them countless times in the almost-hundred years of his too-long life. Places of evil, where masked priests worshipped at the altars of false and dangerous gods. He knew too well what sort of things they intended with the boys that they had taken—and what they had already done. Adaman knew much of sorcery—more than any man should. Over the course of his too-long life, he’d learned to detect the stink of it. Evil had a smell, a character. He’d detected that character in the voices of the men he’d overheard whispering in the village inn that morning, in the way they put their heads together, dark eyes flitting about the smoky common room. “It’s almost time…” The big man had said, slouching into a seat not half a dozen paces from where Adaman sat, unmoving in a darkened corner. “We try again tonight.” “Tonight?” said the other—a beanpole of a fellow with beady eyes. “So soon?” “The God’s Eye is overhead. Baglan says that is well,” the big man said, leaning in conspiratorially. “He says we want the God to watch.” They had spoken softly, and each in the Rhendish tongue, not the Gurrandhi spoken in the village—the better not to be understood. Though both of them had looked around, fearing to be overheard, neither had seen Adaman. Having broken his fast on bread and sausages, the hunter lingered—as he always did the morning he left such places as the village inn—to smoke his pipe in peace before he and his nameless horse set out on the next leg of their journey to nowhere. “You found the boys?” the thin man asked, eyes darting to either side. “Three,” said the big man. Adaman could not see his face, but from the two fingers missing on his left hand, he thought he must be the village miller. Adaman had passed the mill on his way into town, a fine stone building built right on the Greenbend, its wheels turning in the rushing black water. “Not local, are they?” the thin man hissed. “Great Mother, no!” said the miller. “Corun bought them off a drover down in the valley night before last. He’s had them up in Kingsbarrow since.” The thin man’s face fell. “That means old Baglan’s been at them already.” “You know the rules, Kenver,” the miller said, and held up his three remaining fingers. “Three nights. Baglan says we have to ripen them three nights before we cull.” The common room had been nearly empty. Still, Adaman could scarce believe the brazenness of such men, to speak of such things in the open, in the first blush of morning, when the fog was yet rolling in off the downs. There had been no plan, no question what he must do. Adaman had simply waited for the men to leave, not stirring from his shadowed corner until they left the common room and the noise of their feet on the gravel path outside was gone. The witches who had made Adaman what he was had sharpened his hearing so that almost he could see the two men reach the end of the gravel path and turn in opposite directions when they reached the muddy high street that formed the spine of the village called Glastag, Greenhome. Adaman had had no need to follow them. Everyone in the village knew where Rigmardra was… …where the barrows were. The locals avoided the place like a lazaret. It was haunted, they said, by the shades of the old kings, their vavasors and bannermen, their concubines and slaves…and by men such as the miller and the thin one called Kenver. Sorcerers. Coming back to himself, Adaman saw one of his quarry, and pressed himself flat to the earth atop the ridge overlooking the valley where the barrows stood. The sorcerer was seated on a stone at the base of the largest mound, beside what appeared to be the mouth of the tumulus—a great, uneven black arch. The foul magus wore a cloak of animal skins over his commoner’s weeds, with a deep hood that covered the eyes. To the untrained eye, he might have seemed a part of the wilderness. But to Adaman, he seemed to glow. “Adram,” the hunter prayed, invoking his own god, the god of demise and destruction, of cleansing fire. The god of warriors; of death; and of new life again, after. “Lord God, guide your servant. May my hand be swift. May my blade be sure. Do this, and I will make an offering to you: the deaths of these men. Their blood for the blood they have taken. Their lives for the lives they’ve unmade. Make of me your vengeance. Make of me your blade.” Slowly then, Adaman raised himself from the earth. Remaining on his knees a moment, he saluted the setting sun—for the sun was Adram’s, whatever the priests of Mor and his harlot might say. It was right that he should come upon them at twilight, for sunset was Adram’s hour. This would be Adram’s day. Standing, Adaman darted along the ridge, right hand steadying the great blade slung over his shoulder, left on the hilt of the common sword at his waist. The magus had not seen him. The man had some weapon out across his knees. A crossbow, maybe, or an arbalest. There were at least four men, Adaman knew. The big miller—whose name he did not know—the thin Kenver, and Corun, and Baglan. There could be more, and many more. Adaman knew not how many, nor had he any notion of just how great the mages’ magick might be. In his day, he’d known sorcerers strong enough to raise the dead, great enough to bend light and time itself. But others he had known had no power at all, only dreamed of power, or else pretended to it. And men did not need power to be dangerous. But Adaman had a power of his own. Coming to a place where the descent was steepest, Adaman leaped, still holding his swords to stop them rattling in their scabbards. It was half a hundred feet to the valley floor. Adaman landed lightly as a feather. Still the magus had not seen him. That was well. The valley was a long, deep cut, with stone walls high on either side, one of many scoured across the highlands by the retreat of glaciers in the Dawn, when Rök was forged. All the world had been sheathed in ice—so it was said. All agreed it would be sheathed in ice once more, when the sun went out, though none agreed when that day would come. The last and greatest of the nine barrows lay at the head of that valley, not a free-standing mound, but a hillock piled against the head of the valley proper. The grass that carpeted the valley grew to half the height of a man, had gone gray and brittle with the press of coming winter, had grown in patchy tussocks like a boy’s first growth of beard. Still, it was enough to conceal him. Almost enough. The magus saw him, scrambled to his feet. The fool forgot to cry out, raised his arbalest. Fired. Fast as the bolt was, Adaman was faster. He drew his sword—the common sword that hung from his belt—and slashed the bolt from the air before it could strike his face. The shaft spun away to the right. The sorcerer stood no chance of reloading. He barely dropped the crossbow before Adaman was on him. Adaman left him no time to so much as draw his knife. One hand on the pommel for added force, Adaman thrust the curving sword into the mage’s black heart. The hunter ran the man back into the steep face of the hill, sword caught between his ribs. Adaman felt the shock of impact as the man struck the hill, felt his blade pass through the man and pierce the hill itself. The bright ring of metal on metal filled the air. That surprised Adaman, but he kept his focus. Red blood ran from the mage’s mouth. The hand that had gone for his knife fumbled. Adaman did not take his eyes from the sorcerer’s face. The old familiar rage—kindled by the sight of that Imperial airship—had caught in his belly. The Lion’s Dog, that was what they’d called him. But that was so, so long ago. The magus sagged. His teeth bared, Adaman did not take his eyes from the wizard’s face until the light had left his eyes. Then Adaman stood, looked up at the black arch overhead. It was not stone, as he had suspected. Standing over the body of the slain sorcerer, he reached out, touched the lip of that door into darkness. It was metal. His ears had not deceived him. The toothless hag that had sold him dried meat and bread for the road—the woman who had told him of Rigmardra in the first place—had told him that the barrow-builders laid their kings in their ships, sealed and buried whole vessels in the highlands. Ships were more common in those days, so Adaman had always heard. Still, he had scarce believed it. It seemed madness to him. A waste. A shout and a cry sounded from deep within, shook Adaman from his study of the gate. Adaman had ventured into such places a thousand times before, into the deep places of the world, where the light of the sun—Adram’s light—did not reach, save for what little of it he brought with him. But he did not fear the darkness, nor what lay in that darkness. It would be made to fear him. Common sword in hand, he crossed the threshold, felt a dry wind lift his weather-stained cloak, tug his long, dark hair back from his bronze face. The ground beneath his feet was uneven, for the passage of so many years had carried the earth into the chamber, sloping down toward a round inner door. The roof above was all of ridged black metal, sloping down to meet that inner gate. By the end, Adaman could almost touch it. Another cry sounded from inside, and the rough voice of a man before the cry was choked off. Fearing he was too late, Adaman forged past the inner gate, entered a chamber like a tube, the floor roundly flowing into walls and ceiling, the all of it clad in dark metal. Each step rang brightly, despite the hunter’s best intentions. “The cord, Corun!” A man’s voice floated from within. “Hold him down!” Adaman halted at the next door, peered through it. The hall within was canted at a shallow angle, rising to the left, sinking to the right. The ancient highlanders who had entombed the ship in the barrow had not leveled it properly. The sorcerers had set rushlights along the floor, and hung charms from the sloping ceiling, chimes wrought of hollow bone. Careful not to disturb them, Adaman wove his way down the hall, moving slow so as to make as little sound as he was able. The sorcerers had clearly been in that place a long time. As he reached the end of the hall and came to the next, he saw a bank of tallow candles lighted along the opposite wall, their fat running in tendrils to puddle on the floor. More bones were set amongst them. Skulls. Thighbones. Pelvises. More of the bone chimes hung from the ceiling, hands held together by lengths of twine. On more than one, Adaman saw the blackened remains of what had been little ears, set up to listen for the approach of foes. Such charms were false magic. There was no power in them. That made them all the more terrible. “Hold him down, I said!” The hunter reached the final gate, and peering round its jamb saw the inner sanctum, the tomb of the barrow king. The room was broad and open, high ceiling barrel-vaulted, walls lined with shoals of melting candles, decorated with bone. Standing in the center of the far wall was a coffin of iron and clear glass. Within it, the mummified remains of a body lay, utterly desiccated, skin dark as onyx, long hair white as snow. Of gold were the rings upon its fingers, its armlets, anklets, and the necklaces it yet wore. Of gold, too, was the circlet set upon its once-noble brow, set with square-cut rubies. It was the barrow king, its body still intact, unspoiled by looters despite its having languished there for long millennia. The body had the look of the elderkin about it: the black skin; the pale hair; the long, pointed ears. Had the Eternal ruled these lands in days of old? Perhaps the toothless woman in Glastag knew his name, or knew his kingdom, or knew how to count the long years since his dominion. Perhaps no one did. No one, that is, save the cult of pagan worshippers kneeling before his tomb. There were eight—the man on the door, the man Adaman had already killed—made nine. Nine were the Sons of Mor by the Great Mother, and Nine their sister-wives… “Maelung!” they chanted, all as one. “Maelung! Maelung! Lord and lover!” “Lord and lover!” their leader cried. “Come!” “Come!” the others echoed. “Come! Come!” Maelung? Adaman thought. Maelung was one of Mor’s nine sons, the demigod king of Cahaen, one of the Nine Kingdoms of Rök in its Dawn. But Cahaen was far away, they said—if it ever existed—far to the west, beyond the Grand Wall. Farther than any man of Rhend had ever traveled, farther than any ship of Qorin had ever sailed. He could not be buried in the highlands of the bitter south, nor in so drab a tomb. These fool pagan sorcerers were deluded. But even delusions were perilous where magick was concerned—and perhaps especially delusions. “Lord, hear us!” the headman—no doubt the man called Baglan—called. “Drink the blood that we have brought you! Look upon our sacrifice with kindness! Return as we have returned! To you! To life! To Rök!” They were naked, every one of them, though each wore masks of bone. They each had daubed themselves with soot collected from the burning rushlights, or else with lime. Each had painted patterns on their flesh, on the flesh of one another. They knelt in half a circle before the tomb, hands raised. In their midst, on a woven blanket of red and white, lay the three boys they had bought off their highland drover. The oldest no more than ten. They were bound, bruised, gagged. “Maelung! Maelung! Maelung!” the men intoned. The headman raised the instrument of sacrifice—a needle bound to a length of braided hose. The others continued their chant, breathing the name of the Son of Mor to a drumbeat only they could hear. The headman spoke, singing: Lord of Flesh, of Love, of Gold sleep no more in dark and cold. Drink the blood that we have shared. Take the sacrifice prepared. Lord of Flesh, of Love, of Gold sleep no more in dark and cold. Walk once more in light of day, drive our enemies away. Lord of Flesh, of Love, of Gold sleep no more in dark and cold… Adaman wished that he’d had the sense to bring the watchman’s arbalest. He might have taken one in the back from the safety of the inner door. He stood transfixed, unable to move, unable to look away, as the headman—Baglan—thrust the needle into the first boy’s shuddering neck. There was no blood. The blood was in the hose, the coiling thread that ran from the bound sacrifice to the glass sarcophagus that held the sleeping barrow king. For the first time, Adaman marked the witch-lights that shone in the wall beside the tomb of the ancient king, blue and white. Adaman understood. They meant to flush the child’s blood into the corpse in the glass coffin, and so stir it to new life. Such a thing was possible, if the corpse had been rightly mummified—and this one had. But Adaman had seen enough. His horror found his courage, his courage his rage. Not bothering to muffle his footsteps, he strode across the floor of that black sanctum. Too late, the mages turned, and saw him standing over them: the tall Numorran, black-haired, bronze-faced, stern and scarred. Beneath his faded cloak, he wore a quilted gambeson, once black, now gray-green. Greaves wrapped his long legs, and he wore a vambrace on his right arm—but it was the left that drew the eye. The gauntlet, pauldron, and manica that sheathed that arm was white as bone, as ivory, a jointed construction of delicate plates—claw-like—that moved as he moved. It was this hand that seized the nearest sorcerer, grasping him by the throat. The pale arm gleamed with witchlights of its own, and at Adaman’s command a bolt of lightning coursed through the mage’s flabby flesh. Only after he fell smoking did Adaman recognize the nameless miller. His curving sword flashed then, cutting right then left. With each stroke he tore the throats from the men to the miller’s either side. The others, startled, scrambled back, grubby in their nakedness. One, a big man and stronger than the rest, rose clutching the knife that he’d intended to cut the throats of their victims when all was done. Tall though Adaman was, this magus was taller, broader. He lunged, but Adaman parried his knife with ease, hewed at the big man’s arm. Blood spattered the metal floor, and the big man staggered back, tearing the mask from his face to better see. Adaman recognized the man from the smithy that had reshod his nameless horse. “You!” the big man said. “What are you—you should have minded your own business!” Adaman said nothing. They were ordinary men. That was the worst part. All of them. Ordinary men. The man passed the knife from one hand to the other, lunged again. Adaman beat the knife from his hand with his own blade, pressed forward. The big man staggered back, tripped over the boys they’d laid out for sacrifice. A shot lanced past Adaman then, red in that dark place. The shot went wide, and Adaman rounded on the sorcerer who had cast it. The others had all gathered weapons laid about the tomb, bright swords with pale blades and gilded handles, golden wands with eyes of flame. One such eye lanced at him again, caught Adaman in the shoulder. He snarled, rounded on the man. The mage’s next shot went wide, and Adaman leaped at him, knocking the wand from the wizard’s hand before he rammed his blade into the man’s chest. It was the thin man from the inn, the one called Kenver. “Stop!” the headman was on his feet, face concealed by the face of a skull too small for him, his body coated with lime, his dark hair wild. In his hands he clutched a weapon of the Dawn, like a crossbow without the bow. Its stock was horn, its body gilded steel, its price beyond the reckoning of princes. And its shot was death. “Name yourself!” the wizard said. “Baglan,” Adaman guessed, and from the way the naked sorcerer shuffled, he knew that he had guessed rightly, “you cannot raise the dead. Not like this.” Blood red as the finest vermillion glowed in the cord that ran from the eldest child. They were wasting time. Four of the mages yet lived. “That is what you think!” Baglan said, shouldering the arquebus. “We have quickened their blood by torment. Three nights beneath the God’s Eye. We have said the proper words. Done the proper deeds. Lord Maelung will rise again!” “That isn’t Maelung,” Adaman said, not lowering his sword. “That is some mountain king of the elderkin! Are you blind?” “You know nothing!” Baglan said. “Your little mind can scarce conceive what it is we do.” Adaman’s eyes went to the boys lying on the floor. One was surely dead, already exsanguinated. Well he knew the bite of the witch’s needle. Well he recalled the pits of Magoth. His collar. Azara’s bed. “I know exactly what it is you do.” Such was the tenor of his voice that Baglan faltered. The arquebus drooped—if only for an instant. “Who are you?” Adaman did not answer. “That thing, on your arm,” Baglan said. “It is god-make.” Still Adaman was silent. “Give it to me!” the headman said. The other mages had spread out, formed an arc around and before the lonely hunter. Four men, Adaman counted. His shoulder ached where the wand had taken him. Only four. “Name yourself!” When still the hunter said nothing, Baglan aimed his arquebus over Adaman’s shoulder. Fired. The shot split the dark chamber like a wedge, bright as the rising sun. “Speak!” Adaman only stared. “Kill him, Baglan!” said the big man, clutching his wounded arm. “We’ll feed his blood to the god!” “Kill him!” “Kill him now!” Baglan shouldered the ancient weapon, aimed it square at Adaman’s chest. He never got the chance to fire. An unseen hand slammed into him, knocked the weapon back and upward. The shot sliced the ceiling, and Adaman seized his moment, rushing in, sword drawn back for the thrust. His curving blade plunged into Baglan’s belly, and the headman stumbled back, heel catching on the dais at the base of the glass sarcophagus. He fell, and Adaman’s sword was almost wrenched from his hand as he fell. The hunter staggered, and as he staggered, Adaman felt the bite of a blade in his own back. Red pain flooded his senses, and he cursed, turning, found the big man staring down at him. “Careful, Corun!” said one of the others. “He uses magick!” Adaman stretched his eyes wide, and a shout of force hurled the big man from him, clear across the crypt. The hunter’s whole body went cold, colder than his meager blood loss could account for. The power sucked the life from him, drew from the fire in his blood. The knife was still in him. He had to draw it out if the healing was to begin. If he drew it out, he would have a weapon. Reaching back behind himself, he found the bone hilt of the mage’s dagger, tugged it free. “What is he?” asked one of the mages, drawing back. “A witch?” Boom. The sound rose from deep in the bowels of the buried vessel. A hollow, metallic boom, as if the bolt of some almighty door were unlocked. “What was that?” asked one of the naked men. Cold laughter bubbled up behind Adaman, and he looked back, half-expecting to find Baglan still alive, clinging to life by some fell art. But the flabby magus was dead, his blood red upon the dais. Horrified, Adaman turned to regard the corpse in its glass sarcophagus. The children’s blood had not stirred the mummy to new life. A voice—deep and black as the underworld—filled the chamber, seemingly issued from its walls. Its words seemed to Adaman to be the speech of the elderkin, but he could not understand it. Still, he understood its meaning plain enough, as music in his mind. You do not belong here, the undead king seemed to say. You should not have come. “Maelung!” one of the sorcerers cried. “Lord and lover, god!” Already Adaman could feel the sinews in his back beginning to knit. The witches had given him that gift, at least. The bleeding had surely stopped. He dropped the bone-handled knife, placed one hand on the baldric slung over his shoulder, the other on the hilt of the great sword slung over his back. He had hoped not to need it. It was a famous blade. If word got back to Qorin, or to Parha, or the Wall, that the White Sword had been seen in the highlands beyond Rhend, the Empire would surely send its ships. But word would not get out. Doors opened in the rear of the crypt, one to either side of the dead and dreamless king. With his heightened senses, Adaman surely saw them first. Tall they were, taller than any mortal men—tall as the lords of the elderkin in ancient days before the fall. Black-skinned were they as their makers, limbs bound in rings of gold, their fleshless bodies painted with intricate designs, the like of which Baglan’s crude markings were only the faintest, foulest imitation. They were clad each only in breechclouts of white silk, time-eaten and frayed. There were two of them, each holding a hooked and wicked blade. Adaman knew what they were at once. Barrow-dwellers. Again-walkers. Wights. The deathless servants of their long-dead king. Their flesh was iron. Their hearts steel. Adaman unfastened his baldric, unslung the White Sword. It was one of the Namsarí, forged in Adom, in Godhome, for Mor’s faithful knights. It was, perhaps, the last Namsar in all creation. And Adaman drew it forth, and lo! It was broken a foot from the tip, so that its end came to a jagged point. Still, it was longer than any sword had a right to be. Longer, broader, sharper…and lighter than any steel. The blade glowed in the dim candlelight, white as virgin snow. Dropping his sword, one of the naked mages rushed forward, dropped to his knees before the wight, hands pawing at its breechclout. “We are your servants!” he said. “Your slaves! We are yours! Do with us as you—” …please. He never finished. The wight’s crooked sword took off his head. In a single motion, it turned its flat-nosed face on Adaman, long white mane swaying. His shoulder ached where the big mage had knifed him, his body ached from his use of the witch’s power. But Adaman raised the Namsar of Godhome, held it high in challenge. Faster than human seeing, the wight lunged at him. Adaman brought his sword slamming down, felt the blade connect. The White Sword needed no sharpening, for no stone could make it sharper than the forges of Godhome already had. It could cut anything and never dull, for nothing could blunt its edge, nor break it—save the one thing that had. The wight’s blade fell in two pieces, and the iron demon had no recourse but to batter Adaman aside. Its fellow moved with great speed, its sword cleaving the other mage in two near as easily as if the weapon were a Namsar itself. The big man with the wounded arm—the last of Baglan’s foul brood—turned and made for the door. He could not have gone more than three paces before the wight overtook him, and opened him from shoulder to groin. Adaman hit the wall, knocked skull and candles to the floor. The wight whose sword he had destroyed advanced on him, moving slowly, threateningly. The black voice was still speaking, filling the chamber with its malice. With a cry and a shout of power, Adaman lunged. His will staggered the fell creature, lifted bones and candles and tattered clothing from the ground. The Namsar flashed, clove through the wight’s black hide, split its iron bones and golden bangles. It fell at Adaman’s feet, and the objects his will had lifted fell with it. A dreadful cold leeched through the hunter then, and he faltered. The second wight rounded on him, moving with a speed and terrible vengeance. It was all Adaman could do to raise his sword in time, even with his more-than-human reflexes. His parry severed the monster’s arm entire, and its crooked sword fell with nerveless fingers. Undaunted, unfeeling, the wight pummeled Adaman with its other hand, and the hunter skidded across the floor, head ringing. The Namsar fell from his hand, and the one-handed wight loomed over him. It grabbed at him, and Adaman grabbed at it—seized it with his left hand. Lighting coursed once more through the godforged armor, poured into the monster as it stooped to seize him. It fell smoking just beside him. The rest was silence. Adaman lay there only a moment. He had forgotten the boy. Almost forgotten. Shivering, aching, battered and bloody, he limped across the floor to where the children lay. The one was certainly dead, the second dying. He untied him as gently as his fumbling hands would allow. Applying pressure, Adaman drew out the witch’s needle. “Keep your hand here,” he said. “Press hard. You understand?” The sight of him fanned the fury in Adaman’s guts once more, and he untied the third boy. Neither had it in them to move…not after all that they had suffered. “You,” the black voice said, speaking the common tongue. Adaman looked up, looked into the face of the long-dead barrow king. “You are witchmarked,” the dead king said, voice filling the chamber. The two boys shuddered. “You should be dead,” Adaman said. “You are no haeling, your bones should not remember.” The barrow king did not move, nor did he give any sign. “Our will endures,” he said, voice emanating from the room entire. “We endure. Our spirit preserved in light and crystal.” Adaman said nothing. The Namsar lay not far from where he knelt with the poor victims. He found his feet. He had heard of sorcerers trapping their spirits in crystal to escape death. He had never seen it done. “You are witchmarked,” the barrow king said once more. “We see the shadow on you…Numorran. The weight…” Adaman could feel the witch-king’s fingers in his mind, saw his memories as the dead thing lifted them, turned them in his hands. The grottoes of Magoth. His collar. His chains. The witch’s needle. Her lust. Her blood on his hands. “You need not bear it alone,” the barrow king said. “Let us bear it for you. Take it from you.” There were two suns in the sky, red and white. Numor. His home. The world he no longer remembered. His father’s face. His mother’s tears. “You need but take us out of here,” the monster said. “And we will bear your memory. Ease your pain.” He leaped from the deck of a Qorinese airship, caught the rigging with one hand. The ship was going down in fire. The earth rushing up to meet it. He shoved the memories away, but every time he tried, the wight seized another, presented each to him in turn. Adaman shut his eyes, but shutting them did not stop the visions. “You will be a king,” the barrow king said, “as we were of old…” Winged Lion banners flew beneath the standard of the Parhan King. “Samar!” the men all cried. “Samar! Samar!” “Samar…” Adaman felt his hair floating from his shoulders, felt the power gather in his chest. He took a step, and the metal of the floor broke beneath him. The crack traveled, reached the casket and the body of the barrow king. Glass shattered, bones splintered, and the witchlights around the sarcophagus sputtered and died. Adaman’s hands were shaking, with fury and with cold. He had not heard the hated name, not in years. Not in decades. He had never wanted to hear it again. # He carried the boys one by one from the barrow, fed them, clothed them, buried the one who had died. It would be days before the other two spoke. He would not take them back to Glastag—for all he knew, there were yet more of Baglan’s coven in the place, more monsters in man’s shape. While the boys ate and shivered by the fire, Adaman gathered the riches of the barrow and laid them on the grass outside. Knives and swords there were, and rings, bangles, bracelets…cups and plates and drinking horns. Then there were the crystals, great sheets of diamond shot through with flaws by the mage’s art. He had shattered them into pieces, and set the pieces in the sun. Let men find them, take them, make other men cut them down for jewelry. With every cut, the spirit of the barrow king would be destroyed a little more, until ten thousand little pearls of his awareness remained in the coronets of queens and on the hands of merchants’ wives. The arquebus Adaman kept for himself. He set aside parcels for both the boys. Enough—and more than enough—to buy them some proper home. Apprenticeships. New lives. When the sun rose once more in the north, Adaman set the boys both upon his nameless horse, and turned them all to face it. He would take them north, far from Glastag and the highlands, far from the horror they had faced. In his secret heart, he prayed a prayer of thanks to Adram—whose sun it was. Together then, they left Rigmardra, never to return.

I’m just getting to “Demon in White”, book 3 of Sun-eater, and I am absolutely floored. Ruocchio has easily become one of my absolute favorite creators! So psyched to see him here!